Enchanted Lands | Amy Lincoln, Anna Ortiz, Jen Hitchings

May 23 — Jul 20, 2024

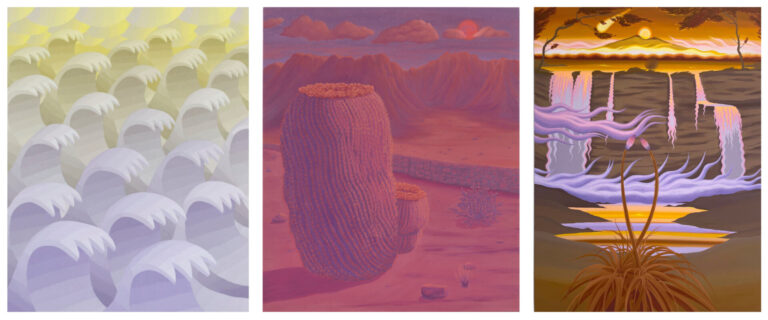

Surrealistic maximalism thrives in these three artists’ paintings as awe-inspiring counterbalances to incomprehensible and terrifying daily narratives. Paintings by Jen Hitchings, Anna Ortiz, and Amy Lincoln find conversation in incandescent color palettes, playful symmetry, and puzzling optical effects in compositions that depict recognizable elements in wilderness scenes unpopulated by humans. But these artists borrow nature’s motifs for different purposes that are distinctly separate from nostalgic plein-air practices or regional documentation. Exhibited together, the paintings showcase wide-ranging politics in contemporary landscape painting, where imagination leaves sublime romanticism and pathetic fallacy behind in favor of highlighting moments when boundaries crumble between representation and abstraction.

Anna Ortiz builds compositions populated by totemic, omen-rich objects and places that collage her psychological journeys while sleuthing her Mexican-American heritage. Mesoamerican statuary, isolated vistas strewn with ruins and architectural detritus, and culturally symbolic botany—Nopál; Biznaga; Saguaro; Blue Agave— unpack and decolonize narratives of migration and estrangement in borderlands by bringing these objects, entities, and place names back into sacred space. Metaphysics in her paintings are evoked representationally, by depicting Aztec-powered mashups of volcanic eruptions, lunar eclipses, and pyramids for example, but also by Ortiz’s passion for monochromes that favors adjacent, limited color palettes that “slow time down, expand, and elongate” viewing attention reminiscent of geological and prehistoric time. Smooth, matte, low-contrast surfaces create a uniform, immersive viewing experience that “never lands in one spot,” as the artist says. Lines between recognizability and the unfamiliar are seductive in painting, just as they are dangerous when one straddles worlds as a bi-cultural person. Horizon lines in Ortiz’s paintings are “always moving, like rainbows.”

Jen Hitchings’ paintings are fictional composites depicting “places invented on ideas driven by composition.” Her landscapes are compositionally informed by mythic and mystic philosophies not to imbue her paintings with syncretic or idealized magic, but to “investigate how people live their lives.” Recognizable elements and views —a blossoming succulent; waterfalls cascading into lakes and rivers; sunset’s effects on trees—root the paintings in recognizability, but from here narrative implications clearly stop, instead emphasizing the slippery ways that human cognition and interpretations of place inform perception. Hitchings’ high-contrast, sharp-edged paintings study distance and physical space in relationship to the body and psyche. Parallels between human and inanimate natural forms embed biological and sexual features into her works, that are also designed using ratios, numerology, and fractional geometry after collaging photos she has taken to build crude sketches. She works with color sequentially as her bodies of work develop, embracing one color family per painting (ie “blue painting,” “brown painting.”) The effects are jarring, disorienting, and stark; her distorted lines oscillate all over her canvases, feathery as Charles Burchfield and curly as Leonora Carrington. Her paintings foreshadow urgency and import, as if epiphany lurks around every bend.

Amy Lincoln’s paintings are paradoxically earth-based and celestial, reflective and refractive. Each painting’s visual grammar is designed to create perceptual shifts that are as the artist says, “attuned by the long stare,” by challenging logic with illusion. Motifs are not spiritually-oriented, instead selected for their infinite ways to portray light and space—seascapes that study water and air; skyscapes that study clouds and sun. While her paintings’ optical effects are dense and richly layered, Lincoln restricts her subject matter to a minimal array that aims for “quieter, simpler, decluttered” interpretations of how ephemeral light can be. That said, her paintings are overtly unrealistic: light sources cast “false,” overly-luminous or totally-absent shadows; exaggerated perspective points and landscape features disrupt trustworthy visual filters. Lincoln says that “color and value relationships are imperative” to maintaining tensions between controlled and organic forms. She chooses three colors to mix per painting. Meticulously planned mockups shape orientation and color, while transparency and incandescence are achieved through layers of gradation that depicts “light moving across a surface.”

Lincoln’s studies of light and color can be called transcendent only in the sense that they openly invite viewers to consider our own takes on immanence—how divinity might be expressed in our material world— but she does not make her paintings with this in mind. Hitchings and Ortiz, on the other hand, implant emblematic shapes and signs that trigger subconscious theater. Ortiz summons supernatural powers inherent to ancient histories, and Hitchings’ paintings explore occult platforms. All three artists depict moments of ineffability in ways that simultaneously freeze and release their experiences of change, something that landscapes excel at. Maybe instead of calling them visionary landscape painters, it would be more accurate to say that when Landscape is your mentor, demarcation lines between humans and our physical world are guaranteed to be ambiguous, transgressive, dwindling.

Enchanted Lands opening at Johansson Projects; previews with Anna Ortiz in person on May 23, 1-6pm and an Opening Reception with Amy Lincoln in person on June 7, 5-8pm.

Check gallery website for hours and additional info